Articulations, Transfer Agreements, and Consortiums in higher education

An “Articulation Agreement” is a contract one school signs where they agree to accept specific courses from another school. But what is a “consortium”, how do these impact students, and are schools using all of these levers effectively?

History of “articulation agreements”

Each individual school in the US is a separate entity and, most often, does not have a requirement dictated to them by any outside entity that they must accept the credits from another school. In essence, schools are not mandated to say, “your credits from this other school count here.” This is a very painful truth in America, brought about by years of competitive practices without standardization to empower the masses.

It’s a simple fact – the most expensive colleges are expected to have more prestigious professors and access to the latest research (often due to grants and other accomplishment-driven funding levers), and those professors therefore have access to materials and set up expectations of their curriculum that less funded schools simply do not. The unfortunate result is that, generally, schools expect students who came from a less-well-funded institution (or less prestigious) to not truly understand the same concepts coming out of, for example, Corporate Accounting from a more prestigious institution. Additionally, sometimes the perceived difference between the two institutions isn’t that the content is necessarily different – it might be even the same textbook – but, the difference is instead the rigor applied during the course. Did one course require more homework, projects, or real-world experience? Did one have harder exams?

Regardless, it’s simply important to acknowledge that there is often a perceived difference in quality between the coursework and resulting knowledge obtained at different institutions.

What are “articulations” anyways? And why so many names?

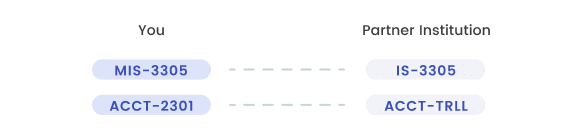

This is where “articulation agreements” come into play. An “Articulation Agreement” is a contract between two schools signed by the Provosts or the Presidents to agree to accept specific courses from the other institution. Many articulation agreements are established in such a way that they only cover specific courses (in essence, “we believe your mathematics department is equivalent to our mathematics department, but your biology department certainly is not”), but some are comprehensive agreements between institutions (this is more common when the institutions are operating underneath the same ‘banner’ or ‘system’, such as “University of Texas” with UT SA, UT RGV, UT Austin, etc.).

Articulation agreements are therefore, in essence, “matches” between two courses across different institutions; or, these can also be known as “equivalency agreements,” meaning, “these two things are equivalent to one another).”

History of “consortiums”, and why are articulations so hard to set up…

One thing that many students don’t think about is that articulation agreements aren’t necessarily easy for schools to set up. And, to be frank, they can take a certain level of political influence to be created… in essence, imagine how difficult it might be for the President of a small, rural, out-of-state community college with very little money and not much free time to meet with and then create agreements with the President of one of America’s Ivy League 4-year institutions. How would they even get the meeting? Then, how would they prove their content meets the standards? To prove this, how many professors might need to meet and know each other ahead of time? Then, how many Deans would need to meet and review the overall curriculum standards, all before these agreements could be made?

Another thing students might not consider is the cost to enforce these individual agreements… once the agreement is made, how expensive is it for the receiving institution (the one that will accept the credits) to implement and enforce it across all of their different recruiting, enrollment, and program-level departments? It is actually not hard to imagine that hundreds of individuals may need to be involved in order to perfectly enforce the agreements made. Yet, the receiving institution (historically) has expected to not make any more money by accepting these credits… the truth is, they (historically) expected to lose money on a per-student basis by being more flexible. In essence, if you pay for 4 years of college with them, that’s a whole lot better to them than you only paying for 3.

This challenge is why we have “networks” (i.e. – “consortiums”).

What is a “consortium”? And how do they get established?

A transfer network, also known as a “consortium”, is a different construct entirely and is formed via a different mechanism. Rather than two Provosts or Presidents sitting down and establishing an agreement between their distinct institutions, a separate organization – either a state (like the state of Ohio), a shared-purpose group of individuals (such as TCCNS), or a private company willing to shoulder the administrative costs (such as Acadeum) – can create a centralized network and oversee the administration of it. The administrator of the network/consortium would therefore oversee and incur the cost of creating an initial subset of courses that they have sufficient knowledge in and can vet, as well as the actual vetting/validation of the unique curriculum of each new partner school and their coursework to be accepted into the consortium.

The benefits of a consortium

The way individual schools see a network is this: each school that joins into the network is agreeing to accept credits of specific courses from any institution that the network administrators vet. That said, an individual school does not have to match 100% of their curriculum into the network – a school might choose to join a network but only match 20 of their courses into the network, saying in essence, “these 20 courses are standard enough that, if these network admins say it’s good from this other school, we’ll go ahead and take it. We trust the network admins.” Yet, they might offer 400 courses to students, and only ‘match’ 20 into the network.

The benefit to the school is that they can start to standardize their simpler articulation agreements via the consortiums and increase their “transfer friendliness” in their regional, political, or technical space. To the school, this is a mechanism to help them attract new students who are looking to transfer their existing credits into a new institution. Other benefits for a school are:

- Increase transfer enrollment

- Improve graduation rates (as students advance to graduation faster)

- Improve name and brand recognition

The benefit to the student is that they are given more options to work with when looking for a new home to finish their degree at, as consortiums allow them to move their credits around more flexibly than in situations where a consortium doesn’t exist. Other benefits for a student are:

- Less time retaking coursework

- Start career (or increase earnings) sooner

- Peace of mind by eliminating the confusion of what transfers

- Feeling welcomed as a transfer student and part of your new institution

The challenges with consortiums

Unfortunately, consortiums don’t solve all challenges just because an institution agreed to be a part of one… even though a school might match their coursework into a consortium, students aren’t by default given transparency into its existence. And, a consortium doesn’t just magically happen for an institution, either… the administrative burden we talked about earlier – where hundreds of people might need to be aware of the agreements in place, collectively ensuring they are enforced – still exists and doesn’t just go away.

The sad truth of America’s higher education institutions is that most do not have software in place that supports consortiums, nor do they have software that helps prospective students evaluate their transcripts against them when transferring in. In fact, many schools don’t even have the ability to run a basic transcript evaluation automatically against their 1:1 articulation agreements (other than by spreadsheets and faculty willing to help by email).

Unfortunately, this lack of automated processes may lead to transfer credits getting matched by hand for one student and credit is given for that course, but the next student who comes in with the exact same course might not get the same treatment. Now let’s be clear… this isn’t done maliciously. We’re not saying that schools have something against individual students, or that they’re trying to discriminate coursework haphazardly. The problem is unfortunately something much simpler – when everything is done by hand by a collective group of individuals that are already maintaining an overwhelming workload of grading, essays, exams, along with research and grant-writing, it’s easy to make mistakes and overlook what was done in the past. Schools need better systems, and they need support to help make decisions intelligently.

How DegreeSight helps

DegreeSight was developed from the very start to solve the complex data and workflow challenges at institutions that are hard to solve by people and money alone. DegreeSight hosts direct articulation agreements for institutions for free, as well as consortium agreements, allowing institutions to create a centralized (non-spreadsheet) web-based platform for their faculty to work through. Additionally, DegreeSight lets students submit their unofficial transcripts (manually entered, and much faster) over to schools for a comprehensive evaluation. Anything that doesn’t automatically get picked up by known agreements, whether direct articulation or consortium-based, will get thrown into a workflow that the schools can use to manually approve one by one. And, we help schools search through and review their historical records to find out what was done last time & minimize the chance that students are accidentally given preferential (or discriminatory) treatment.

But wait, there’s still more to the story

Then again, matching your courses against to internal credit just scratches the surface of the problem… when students submit in their courses, an articulation agreement or consortium might tell them what courses match in, but it doesn’t necessarily tell them how those accepted credits will apply to their target degree. Unfortunately, it’s easy for courses to be “accepted” as elective credits that really get a student nowhere towards real graduation. In essence, you might have a full year of credits “transferred” in, but it can still take you a full 4 years for you to graduate if your previous credits are not applied directly to your basics.

This is another challenge for a larger topic, but let’s just say that DegreeSight is working to help there, too. And we’re doing so in a way that brings transparency to students and faculty to a higher degree than has ever been done before in America. To find out more, feel free to reach out to us at info@degreesight.com.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get Updates And Learn From The Best